Masanori Kobayashi, an expert in ocean and sustainability policy, reviews the latest progress and existing challenges in the international movement to promote a sustainable blue economy through the conservation of marine ecosystems and sustainable use of the ocean’s resources.

* * *

Policy initiatives toward a sustainable blue economy have picked up steam as part of the larger international campaign to concurrently pursue ocean environmental protection, sustainable use of marine resources, and sustainable development. The Tokyo Foundation’s Blue Economy Project brings together scholars from the Sasakawa Peace Foundation’s Ocean Policy Research Institute with researchers in the Tokyo Foundation to explore global developments in the field and study policy options for Japan. In the following, project member Masanori Kobayashi, a senior research fellow at the OPRI, offers an overview of the achievements and challenges of the blue-economy movement.

On June 8 this year, the United Nations celebrated World Oceans Day with a virtual event featuring 40 experts, political leaders, community voices, and entrepreneurs from around the globe. And on July 20, the Ocean Policy Research Institute commemorated Japan’s own Marine Day, which was on the eve of the Tokyo Olympics, with a panel discussion featuring professional sailors and streamed online from Hayama Marina. Both events highlighted the concept of the “blue economy,” noting the critical role the oceans play in every area of life, the impact of climate change, and the threat of marine pollution.

These events served as a reminder of the urgent need to promote a sustainable blue economy. In the following, I would like to highlight the concept of the blue economy and offer an overview of key challenges, initiatives, and future prospects.

Why Is the Blue Economy at Stake Now?

We human beings dwell on land. As a result, many people are apt to forget that the oceans make up 72% of the earth’s surface and 95% of the biosphere (the space occupied by living organisms). Of the 193 UN member states, only 43 are landlocked; the other 150 face or connect with the sea. According to the UN Atlas of the Oceans, 44% of the world’s population lives within 150 kilometers of the coast. Millions rely directly on the ocean for their livelihood, and all of the earth’s myriad inhabitants depend on it for life.

In its broadest sense, the blue economy, though underpinned by an emphasis on sustainability, is considered synonymous with the ocean economy, which encompasses all the wide-ranging economic activity tied directly to the oceans, including fisheries and marine products, shipping, seaside tourism, marine sports and recreation, desalination, seabed mining, and offshore wind power. The value of the ocean economy is estimated at $2.5 trillion annually—slightly below the gross domestic product of France, the world’s sixth-largest economy. Moreover, in its 2016 report The Ocean Economy in 2030, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development projected that the ocean’s contribution to the global economy would double in size between 2010 and 2030.

In the same report, the OECD attempted to broaden our understanding of the ocean economy to include not only the “economic activities of ocean-based industries” but also the “assets, goods, and services of marine ecosystems.” This concept is schematically represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic Diagram of the Ocean Economy

Source: Based on OECD, The Ocean Economy in 2030.

While sometimes used interchangeably with “ocean economy,” the term “blue economy” more frequently refers to the sustainable development and utilization of the ocean’s resources. The Economist has defined the blue economy as “a sustainable ocean economy that harnesses marine ocean resources for long-term economic development and social prosperity while protecting the environment in perpetuity.” The concept and its policy implications are also discussed at length in the OPRI’s 2019 White Paper on the Oceans and Ocean Policy in Japan.

The emergence of the blue economy as a keyword can be traced back to the 2012 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro. Delegates of the small island developing states of the Pacific, on which the marine environment has an immediate and outsized impact, expressed reservations about the conference’s focus on the “green economy,” which seemed to neglect issues of ocean conservation and development. The term “blue economy” duly appeared in the Report of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development. The first global conference dedicated to the topic, the Sustainable Blue Economy Conference, was held in November 2018 in Nairobi, Kenya. Co-hosted by Japan and Canada, the conference brought together more than 16,000 participants from around the world, including heads of state and other leaders.

The Ocean Panel

Another milestone in the effort to tackle ocean sustainability issues multilaterally was the 2018 launch of the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (or Ocean Panel), which began as a Norwegian initiative. Co-chaired by Prime Minister Erna Solberg of Norway and President Tommy Remengesau of Palau, the Ocean Panel is made up of the leaders of 14 countries—each with its own sherpa, or alternate representative—along with the UN secretary-general’s special envoy for the ocean. Informing the panel’s work are an Expert Group of more than 250 members and an Advisory Network consisting of over 135 private-sector, nongovernmental, and intergovernmental organizations across 35 countries. Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga is currently a member of the Ocean Panel, as was former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Upon its launch in 2018, the Ocean Panel embarked on an intensive two-year effort to chart a roadmap for a sustainable ocean economy, commissioning research and holding policy dialogues and other deliberations on a wide range of topics. In 2020, it issued a series of blue papers and special reports, and in December the same year it published a global ocean action agenda, Transformations for a Sustainable Ocean Economy: A Vision of Protection, Production and Prosperity.

In endorsing this agenda, the members of the Ocean Panel each committed to adopting national sustainability plans aimed at managing 100% of the marine waters under their jurisdiction (including territorial waters and exclusive economic zones) by 2025. At the same time, they embraced the global goal of protecting 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030. The members further agreed on 74 priority actions oriented to outcomes grouped under the five themes of ocean wealth, ocean health, ocean equity, ocean knowledge, and ocean finance. Immediately following the report’s publication, the participating countries hosted international events to publicize and discuss the recommendations. In Japan, the OPRI and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs co-sponsored an international webinar, held on December 3, 2020.

The next phase of the Ocean Panel’s activities is still in its planning stages. What are the priority issues that need to be addressed, and what kind of action can we expect in 2021 and beyond?

Marine Protected Areas and Sustainable Fisheries

One key agenda item is the establishment of national targets for the creation of marine protected areas. At the Cornwall summit in June this year, the leaders of the Group of Seven committed to the goal of conserving or protecting at least 30% of global land and at least 30% of the global ocean by 2030. Although not binding, this agreement was viewed as a major step forward.

Under the Aichi Biodiversity Targets adopted in 2010, Japan embraced the goal of making 10% of the waters under its jurisdiction marine protected areas by 2020 (up from 8.3% in 2010). In December 2020, Japan fulfilled and exceeded that commitment by designating four marine protected areas for conservation of offshore seabeds around the Ogasawara Islands, boosting the ratio of protected areas in its exclusive economic zone to 13.3%. On average, however, the world’s countries protect only 7.65% of the waters under their jurisdiction, as compared with 15.67% of the land.

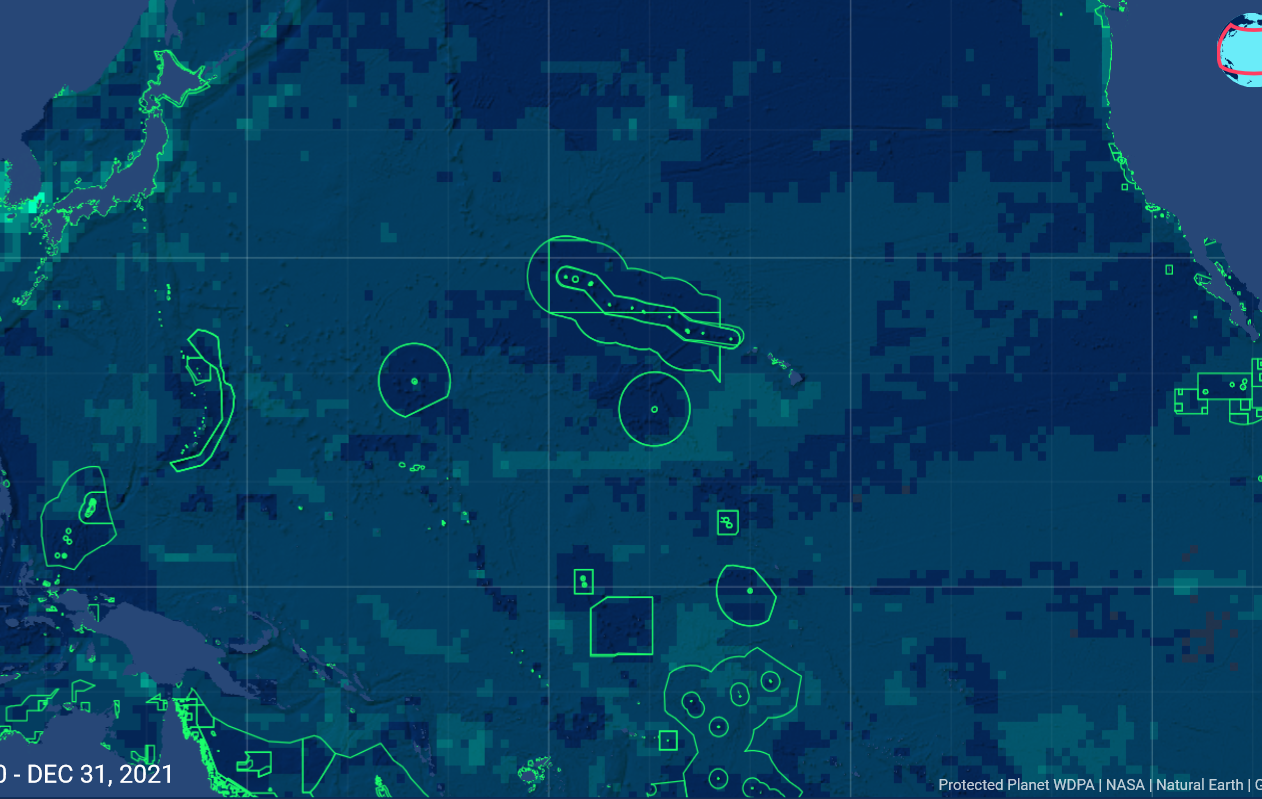

Generally speaking, East Asian countries have been slow to expand the coverage of the MPAs in their EEZs (Figure 2). How can we hasten the process, and how might we go about establishing MPAs on the high seas?

The 30% goal endorsed by the Ocean Panel and the G7 is based on a growing scientific consensus that at least that portion of the global ocean area must be protected in order to preserve marine biodiversity.[1] This figure is understood as a basis for negotiating international agreements, not as a uniform target for each nation. Nonetheless, steady progress in the expansion of MPAs at the national level is essential if we are to reach the global 30% target by 2030. In Japan and elsewhere, moves to expand coastal MPAs will have to be reconciled with fishery management policies, including aquaculture and other measures geared to sustainable use of fish stocks.

Figure 2. Marine Protected Areas in the Pacific

Source: Global Fishing Watch, https://globalfishingwatch.org/.

IUU Fishing and Harmful Fishery Subsidies

Japan’s marine fishing industry shrank by 23.2% between 2008 and 2018. However, during the same period, marine fishery production worldwide rose 24.5%, attesting to rising pressure on marine resources. With some 34% of the world’s fish stocks being overfished, sustainable management of these resources has become an urgent global issue.

The problem of overfishing and depletion of fish stocks has intensified concerns about illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. Production from IUU fishing is estimated at 20% of the world’s total catch, and in some ocean areas it accounts for as much as 50%. Economic losses from IUU fishing are estimated at between $10 billion and $23.5 billion annually. As IUU catches enter the market, they push down market prices for legitimate catches, resulting in substantial lost revenues (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Economic Impact from Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing

Source: Based on materials presented by Takahiro Matsui at the OPRI International Online Symposium “Progress and Challenges Toward Eliminating IUU Fishing and Harmful Fishing Subsidies and Achieving Sustainable Fisheries,” July 6, 2021.

Government fishery subsidies increase incentives for IUU fishing and contribute to overfishing. Worldwide, governments spend about $35 billion annually—about 20% of the value of all marine landings—to support the fishing sector. Without these government subsidies, as much as 54% of today’s high-seas fishing grounds would be unprofitable at current fishing rates. Slashing these subsidies would reduce incentives for IUU fishing and unsustainable fishing practices, while at the same time freeing up funds for other purposes, including conservation efforts and programs to support the livelihoods of low-income fishing communities. On July 15 this year, members of the World Trade Organization signed off on a roadmap for negotiating an agreement to limit government subsidies that contribute to overfishing, IUU fishing, and the depletion of global fish stocks and pledged to conclude those negotiations within the year.

Marine Plastic Pollution

In a January 2016 publication titled The New Plastics Economy, the World Economic Forum released dire predictions from experts regarding the accumulation of plastic in the ocean. The research estimated that without significant action, the ratio of plastic to fish in the ocean, by weight, would reach about 1:3 by 2021, and that by 2050 there would be more plastic than fish. Although international action to tackle the problem is still in its early stages, the revelations have already spawned a widespread movement to rethink our dependence on single-use plastics.

Since then, the government of Norway has helped spearhead the global campaign for stronger international commitments to reduce marine litter and microplastics. It worked with the United Nations Environment Programme to launch an ad hoc open-ended expert group on marine litter and microplastics, which met four times between 2018 and 2020. In October 2019, Oslo hosted a conference on the theme of Our Ocean, at which the Norwegian government pledged to work for a global agreement on marine plastic litter and microplastics by 2023.

On June 1, 2020, the president of the UN General Assembly, Volkan Bozkir, convened the High-Level Thematic Debate on Ocean and Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water). At this meeting, the Alliance of Small Island States presented the Ocean Day Plastic Pollution Declaration, calling for negotiations toward a global treaty to combat plastic pollution, including binding reduction targets. Thus far 79 states have endorsed the declaration and committed to work for a decision at the next UN Environment Assembly (scheduled for February 2022) to establish an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee preparatory to negotiating a legally binding global agreement to combat plastic pollution. The UNEA meeting will be preceded by the Ministerial Conference on Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution, to be hosted jointly by Ecuador, Ghana, Germany, and Vietnam on September 1–2 this year.

A key focus of these efforts is limiting the use of throw-away plastics and promoting recycling of such products. Another is the tracking, recovery, and recycling of nylon fishing nets. Although discarded fishing gear constitutes a significant portion of the plastics polluting our seas, very little has been done in terms of recovering and recycling it. A business venture has been launched in Japan, and a nongovernmental organization is aiding recovery and recycling in Indonesia, but these programs are limited in scope and must be expanded substantially to make a real difference.

Figure 4. Products Made from Recycled Fishing Nets

Photo courtesy of Refinverse Corp.

Decarbonizing Maritime Transport

As wildfires, floods, and extreme weather events increase in frequency and severity, a sense of urgency is informing international efforts to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change. This urgency came through in the ambitious new GHG reduction targets announced at the April 2021 virtual Leaders Summit on Climate, chaired by US President Joe Biden: from the United States, a 50%–52% reduction from 2005 levels by 2030; from Britain, a 78% cut from 1990 by 2035; and from Japan, a 46%–50% cut from 2013 by 2030.

The blue economy is a vital part of this undertaking. Japan and other countries are working to expand the use of offshore wind power with the cooperation of fishers and coastal communities. The International Maritime Organization, meanwhile, has set a goal of reducing carbon emissions from shipping by at least 40% below 2008 levels by 2030 and 70% by 2050. Japan has launched a program aimed at developing zero-emission ships by 2028 through collaboration among the business, academic, and public sectors. The collaborative research and development projects supported by this program will focus on hydrogen-fueled ships, ammonia-fueled ships, ships equipped with onboard carbon capture systems, and super-efficient LNG-fueled wind-propelled vessels. Interest in the use of electric outboard motors is growing in the fishing and marine tourism industries, and the use of renewable energy for shipping, fishing, marine tourism, and port facilities is making headlines.

Figure 5. A Tour Boat Powered with an Electric Motor on the Otaru Canal

https://news.yamaha-motor.co.jp/2020/019895.html

Blue Finance

Funding mechanisms and incentives for investment are vital to efforts to create a blue economy. The debt-for-nature deal reached by the Republic of Seychelles offers a promising model for small island developing states.

In 2008, Seychelles, a group of islands in the western Indian Ocean, defaulted on its debt to creditor countries. After an immediate crisis was averted in 2009, Seychelles and the Paris Club of creditors reached agreement in 2015 on a debt-for-nature swap supported by funding from the Nature Conservancy. In exchange for a restructuring deal worth $21.6 million, the government agreed to use those funds to establish the Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust (SeyCCAT) and to designate 30% of its marine and coastal waters as MPAs (up from 1% at the time). SeyCATT in turn created a Blue Grant fund, which disburses grants ranging from $6,000 to $1.4 million for marine conservation projects. In addition, Seychelles has issued $15 million worth of Blue Bonds, becoming the first country to issue sovereign bonds for the purpose of marine conservation. The bond benefits from a partial guarantee of $5 million by the World Bank and a low-interest $5 million loan from the Global Environment Facility.

Arrangements such as these can also help turn blue-economy enterprises, such as sustainable fisheries, into attractive targets for sustainable investing by institutional and private investors.

Figure 6. Seychelles’ Marine Protected Areas

https://mpatlas.org/countries/syc/map

Japan’s Role in the Sustainable Blue Economy

The overarching goal of the blue economy poses dozens of policy challenges large and small. Prominent among these are international cooperation, cross-industry collaboration, cross-sector partnerships, multidisciplinary research, application of cutting-edge information and other advanced technology, integration of marine data and information, and marine spatial planning.

As an advanced industrial economy and an island nation in the Asia-Pacific region, Japan has a pivotal role to play in promoting and coordinating such initiatives. First and foremost, it has the capacity to help pioneer international and cross-sector partnerships for the funding and implementation of programs and systems to protect ocean and coastal ecosystems while promoting the sustainable use of marine resources. By making the most of our geographical and economic situation to support such collaboration, we not only support marine conservation and the lives of people in coastal communities but also contribute to geopolitical stability by supporting the rule of law and the principles of sustainability in maritime activity, thereby helping preserve the ocean as a global public good.

The Japanese government should position the blue economy as a key component of its Basic Plan on Ocean Policy and a pillar of its policies for development cooperation, with an emphasis on nurturing cross-sector partnerships and cooperation among maritime nations in the Indo-Pacific and elsewhere. Given the high stakes, there can be no question of the need for a substantial expansion in programs and initiatives in support of the sustainable blue economy.

[1] See, for example, Bethan O’Leary et al., “Effective Coverage Targets for Ocean Protection,” Conservation Letters, March 2016, and Eric Dinerstein et al., “A Global Deal For Nature: Guiding Principles, Milestones, and Targets, Science Advances,” vol. 5, no. 4 (April 2019).